Trinidad and Tobago Debate: Should the Christopher Columbus Statue and Other Colonial Monuments Be Removed?

Fiona Nanna, ForeMedia News

3 minutes read. Updated 6:16PM GMT Fri, 30August, 2024

In a small auditorium in Port-of-Spain, the capital of Trinidad and Tobago, a heated debate unfolded late Wednesday as the nation grappled with its colonial past. The focus was on the future of statues, signs, and monuments associated with colonial-era figures, including Christopher Columbus.

The government had initiated a public consultation to gauge whether the statues and symbols linked to the colonial period should be removed. This move reflects a broader global trend where nations are reassessing their colonial legacies, especially in the wake of increasing demands for slavery reparations across the Caribbean.

The debate was animated and diverse, with voices from various ethnic and cultural backgrounds expressing their opinions. Residents of African, European, and Indigenous descent took turns at the microphone, presenting a range of perspectives.

One prominent suggestion was to relocate the Columbus statue to a museum, preserving it for historical context while removing it from public spaces. Another proposal was more radical: some individuals called for the statue’s destruction and suggested a symbolic gesture of stomping on its remains as an act of reclaiming space.

Eric Lewis, a representative of the First Peoples, also known as Amerindians, voiced a critical view, questioning why symbols of colonial rule, such as the Queen on the coat of arms, still persist. He argued for the complete removal of such symbols from national emblems.

The debate coincides with recent governmental actions, including the decision to redesign Trinidad and Tobago’s coat of arms. The new design will replace the three ships of Christopher Columbus with the steelpan, a quintessentially Caribbean instrument, symbolizing a shift towards celebrating indigenous culture and heritage.

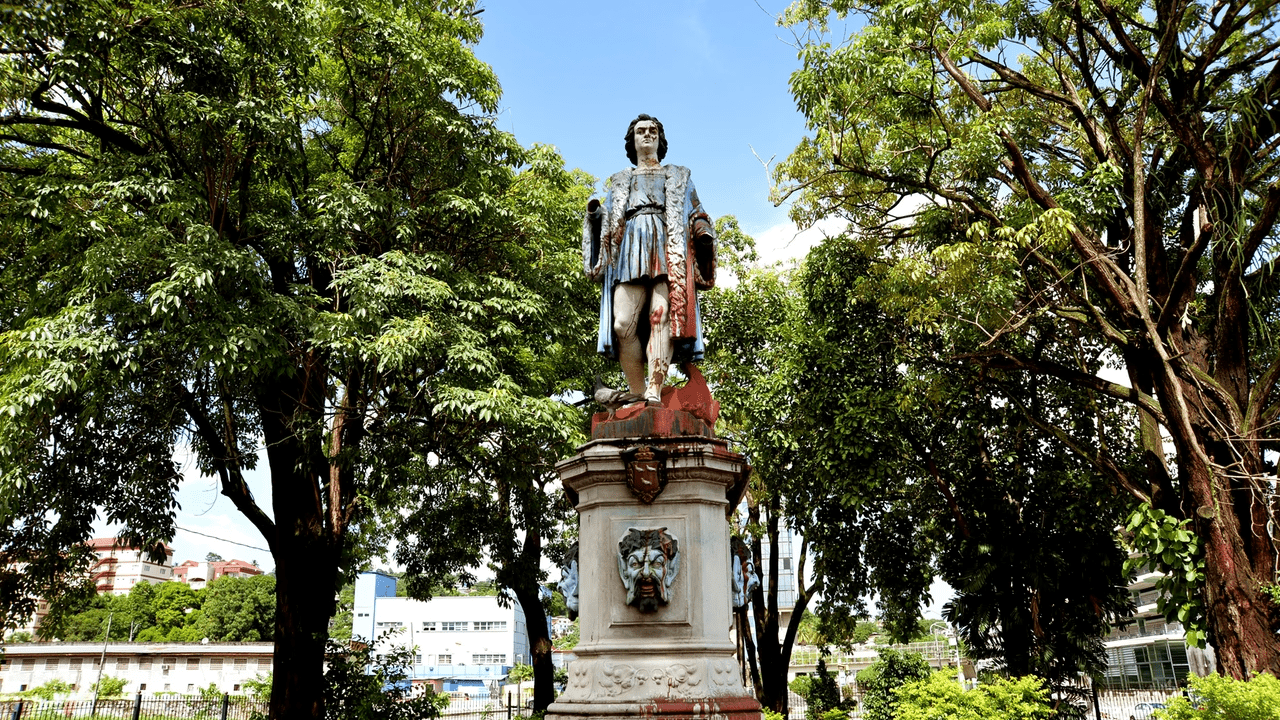

The statue of Columbus, which dominates a square in Port-of-Spain bearing his name, has long been a point of contention. While the National Trust of Trinidad and Tobago describes it as “one of the greatest embellishments of our town,” many locals disagree, viewing it as a symbol of colonial oppression.

The public hearing also highlighted the ongoing struggle with colonial imprints that linger in the nation’s streets and public spaces. The debate is set to continue in Tobago, with nearly 200 submissions received on how to address these historical symbols.

As Trinidad and Tobago seeks to reconcile its past with its present identity, the conversation around colonial-era monuments reflects a larger movement across former colonies striving to redefine their historical narratives.