Stefan Westmann’s Harrowing WWI Combat Experience: ‘I Realized the French Soldier Was After My Life’

Fiona Nanna, ForeMedia News

6 minutes read. Updated 4:15PM GMT Tues, 23July, 2024

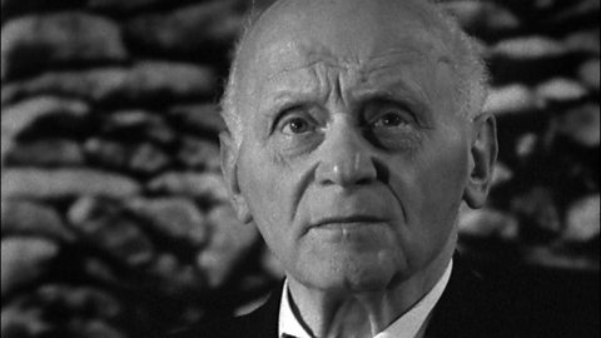

World War One erupted on 28 July 1914, plunging the world into a conflict of unprecedented scale and brutality. In 1964, marking the 50th anniversary of this cataclysmic event, the BBC produced “The Great War,” an ambitious documentary series chronicling the war’s history. Among the 280 eyewitnesses interviewed was Stefan Westmann, a German soldier whose unforgettable account vividly captures the raw brutality of combat and the profound psychological impact of taking a life.

Stefan Westmann, a medical student before the war, had hardly wielded a scalpel, let alone a weapon. Just months into the conflict, Westmann found himself and his German comrades engaged in fierce combat against French forces. During a grim encounter on the battlefield, he came face-to-face with an enemy soldier, both men armed with bayonets and consumed by the instinct to survive.

“For a moment, I felt the fear of death, and in a fraction of a second, I realized that he was after my life exactly as I was after his,” Westmann recounted. “I was quicker than he was. I tossed his rifle away and I ran my bayonet through his chest. He fell, put his hand on the place where I had hit him, and then… he died. I felt physically ill. I nearly vomited. My knees were shaking, and I was quite frankly ashamed of myself.”

By 1964, Westmann had become a respected medical professional and a grandfather. Yet, his recollection transported him back to that battlefield in France, where the trauma remained as raw as ever. Before the war, Westmann had been studying medicine in Berlin. His fellow soldiers, ordinary men from unremarkable backgrounds, had not appeared troubled by the violence they inflicted. “How did it come about that they were so cruel?” he pondered. “We were told that a good soldier kills without thinking of his adversary as a human being. The moment he sees in him a fellow man, he is not a good soldier anymore.”

Westmann reflected on the humanity shared between enemies, wishing the dead French soldier could have signaled his survival. “I would have shaken his hand and we would have been the best of friends because he was nothing, like me, but a poor boy who had to fight,” Westmann lamented. “He had a father, a mother, and perhaps a family.”

After the war, Westmann resumed his medical career in Berlin. The rise of Adolf Hitler in 1933 prompted him to leave Germany and settle in England. During World War Two, he served as a British medical officer in Scotland, thus finding himself on opposite sides in the two world wars. Shortly before his death in 1964, Westmann penned a memoir, “Surgeon with the Kaiser’s Army.” His grandson, Michael Westman, revised the book in 2014, bringing new insights into his grandfather’s experiences.

“The Great War,” a 24-part series, marked a significant undertaking for BBC Two, the corporation’s new cultural channel. Featuring veterans who had written books and other prominent figures, the series also invited older viewers to share their experiences. The response was overwhelming, with sacks of mail brimming with diaries, medals, and mementos.

Researcher Julia Cave, who conducted many of the interviews, recalled the emotional toll of her work. “Nobody who wasn’t in that war could know what it was like,” she said in 2003. “Sometimes men just got lost in the world that they had fought in.”

Westmann remained haunted by nightmares, questioning what might have happened if the young French soldier had been quicker with his bayonet. “What was it that we soldiers stabbed each other, strangled each other, went for each other like mad dogs?” he reflected. “We were civilized people after all, but I felt that the culture we boasted so much about is only a very thin lacquer, which chips off the moment we come in contact with cruel things like real war.”

The brutal reality of close-quarters combat, where soldiers see each other’s eyes before striking, deeply conflicted with Westmann’s inner beliefs. “To fire at each other from a distance, to drop bombs, is something impersonal,” he said. “But to see each other’s whites in the eyes and then to run with a bayonet against a man – that was against my conception and against my inner feeling.”

For further insights into World War One and Stefan Westmann’s experiences, visit BBC Archive on The Great War. Explore more personal stories and historical accounts on History Extra.