Cuban Dissenting Protest Confirms Need for Greater US Intervention

Compared to recent mass protests elsewhere in Latin America, Cuba can seem like a stunned island of calm. But a recent social media-fueled protest against the authorities by artists and dissidents shows that many Cubans are also hungry for change. Contrary to what some hard-line supporters in the United States argue, the new administration of President-elect Joe Biden should not treat this incident as an obstacle to the re-adoption of a policy of engagement with the island led by the United States communists.

The controversy began a month ago, when members of the San Isidro movement – a small collective of artists and anti-government activists – went on a hunger strike to protest the imprisonment of one of their own. A week later, authorities raided his seat and arrested all members, accusing them of violating Covid-19 protocols. The next day, artists, independent journalists and young creatives who had followed the news on social networks gathered in front of the Ministry of Culture to demand a meeting. On the agenda was the need for greater cultural and political openness.

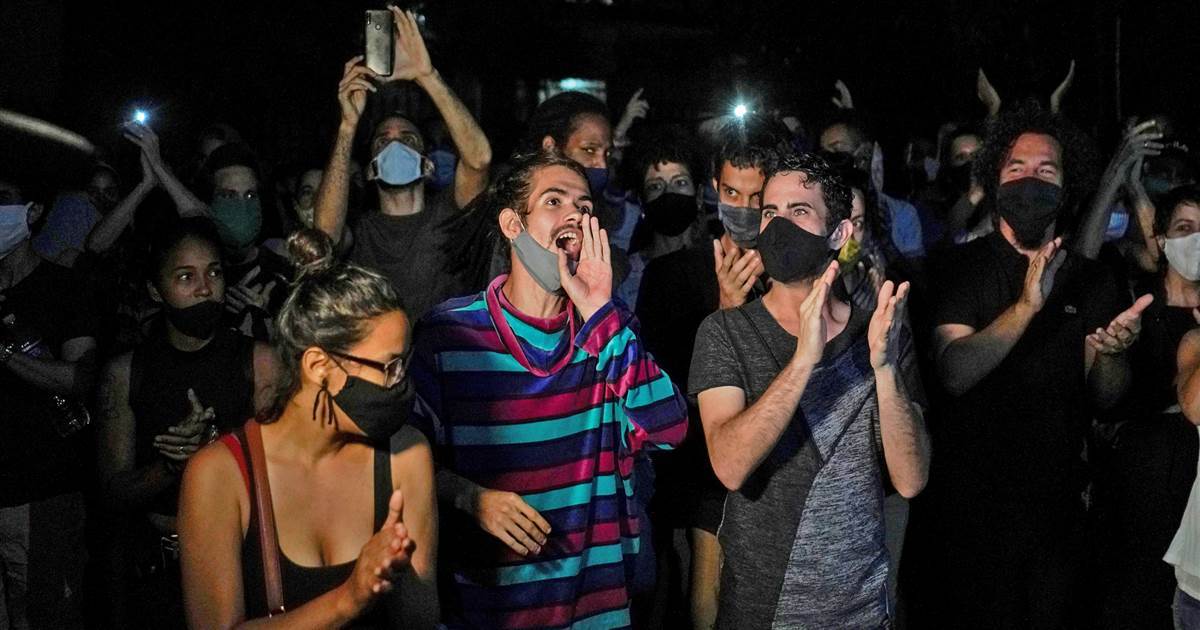

The protest was unprecedented in two respects: its size (up to 500 people) and the fact that it crossed generational and political lines. Additionally, the group was joined by well-known cultural luminaries, although they did not fully agree with the San Isidro movement and its anti-government message. What united them all was the demand that freedom of expression be respected, period. Talks have taken place, but most of the dialogue has since broken down.

For the Cuban authorities, the timing of these events is suspect, because they are at the end of the administration of US President Donald Trump, whose punitive sanctions have hammered the economy. The hunger strike was staged, Cuban officials insisted, in order to dissuade Biden’s incoming team from bringing US-Cuban politics back to a more rational basis. Cuban state media discredited many members of San Isidro as American cronies. A little thoughtful Tweeter of a US official calling them “colleagues” only made matters worse.

While all of this was concocted by American extremists, Cuban officials played the game by responding with muscular and outdated rhetoric. Cuba is a low priority for Mr Biden, amid so many other legacy crises. But what further complicates changing the status quo are sanctions supporters, who argue that the protests are a sign that the “pressure is working” and that recent steps Havana has taken to revive market reforms – like its decision last week, after years of waiting to move forward with a currency devaluation – stream of Cuba’s worst economic crisis in three decades.

Hopefully the Biden administration will learn a different lesson. Cuba’s economic stress has certainly contributed to the malaise on the island, but this distress is more due to Covid-19 and its fatal effect on tourism, as well as the decrease in aid from Venezuela. Any internal changes due to Mr. Trump’s sweeping policies, such as a cap on family remittances, have not been worth the humanitarian cost.

Additionally, Cuba’s latest citizen activist fight is the product of a new, more connected generation on the island who have traveled abroad, including to the United States, and who have Facebook on their 3G phones. These changes were aided by the policy of engagement introduced by former President Barack Obama, not by Mr. Trump’s crackdown.

Washington should listen to the protesters and their supporters. Many insist that US policies of hostility and general sanctions are detrimental to the cause of a more democratic Cuba. History has long shown that the more events inside Cuba are interwoven with the interminably knotty theme of American relations, the more Havana will have an excuse to avoid its citizens’ calls for dialogue and reform.